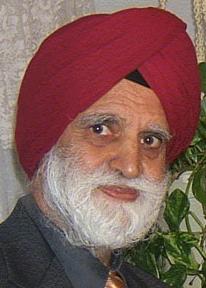

The following is an article written by Dr. I.J. Singh printed

in the Community Profiles Section of The Sikh Foundation.

Dr. I.J. Singh writes,

( Profiles Section of The Sikh Foundation.)

I remember the date August 11, 1960 - when I landed in New York.

The move to the United States was a bit of a fluke. I had just

graduated from Government Dental College in Amritsar. The Murry

& Leonie Guggenheim Foundation announced a competition for

two fellowships to Indians for study in Pediatric dentistry. I

applied. My father wondered aloud what foundation would award

a fellowship to a young inexperienced person with a spotty academic

record. Six months later I was on my way to New York.

The cabbie from the airport told me he was a Jew. I didn't know

much about Jews. So he invited me to his home for Sabbath dinner

and I learnt about the extraordinary kindness of strangers and

the complex mosaic that is the contemporary American society.

After the fellowship I stayed to pursue graduate school. The

University of Oregon was a fraction of the cost at New York University

or Columbia University. So to Portland, Oregon, I went. I had

to look at a map and find out where Oregon was or that there was

another Portland in Maine.

I acquired a Ph.D. in anatomy from the University of Oregon Medical

School and a D.D.S. from Columbia University. The professional

pursuit was not always easy. I was a graduate student during the

day while working at night at minimum wage (at that time $1.25

an hour), processing several hundred rolls of film overnight.

Sikhs are not new to America; the first Sikhs arrived in this

country over a hundred years ago. But they were mostly farmers

and laborers. Educated Sikhs started arriving here after the British

left India, when opportunities in Great Britain dwindled and gates

to America opened through its many scholarship and fellowship

programs. When I came to America in 1960 there were probably no

more than two or three recognizable Sikhs in New York and that

is counting me.

Oregon was even more isolating. But driving around Portland in

the early 1960's, one day I saw a sign Punjab Tavern. On entering

I encountered an old lady behind the bar. She told me that when

she was a little girl, there were Sikhs in the area who used to

frequent this tavern that was owned by her father. There were

racial problems and all the Sikhs had gone to California or Canada.

In Oregon it was not uncommon for people to see me a lone Sikh

with a turban walking about and their missionary zeal would be

aroused. Here was a soul that needed redemption. They would invite

me to their churches or schools to speak on Sikhism. Initially

this posed a problem. What I knew of Sikhism I had learnt primarily

by osmosis by living in a Sikh society and a Sikh home not in

any systematic fashion. Of India and Indian history I knew mostly

platitudes. These invitations in a sense challenged me to either

discard the outer trappings of Sikhism or to learn why I was the

way I was.

I became a U.S citizen around the time that the ultra liberal

Hubert Humphrey ran for the Presidency, the Vietnam War was in

full swing and the campaign for racial justice was catching our

imagination.

In the early 1970's thousands of women and some men, led by icons

like Gloria Steinem, marched down Fifth Avenue in New York to

demand gender equality. Of the less than half a dozen recognizable

Sikhs in New York at that time, I may have been the only one at

the parade. Suddenly, from the leaders of the procession, one

woman spotted me and yelled, Come join us, your women need this

more than we do. I walked in to march alongside her. I tried to

tell her that women in India had more rights under the law and

that there were more women physicians and politicians in India

than in America. She reminded me of their lack of power in the

Indian society and family.

I marched for racial equality and against the Vietnam War, although

gingerly. I was not yet an American citizen and was afraid. But

this has always been an open society. The year I came here '1960'

was the first ever televised debate between Presidential candidates

Richard Nixon and John Kennedy. The questioners were blunt, the

answers were as honest as politicians ever give, and the postmortem

of the debates by journalists absolutely ruthless. I ruefully

wondered if Indian society could ever be so open. I still wonder.

Racial discrimination touched us all although the policy was

not consistent across the country. I joined a rally against George

Wallace, the segregationist governor of Alabama who was then a

candidate for the Presidency. He saw me and I think he was flummoxed.

Most Americans have generally been only minimally knowledgeable

about Sikhs or Indians. Many people would accost me on the street

in my earlier days and would wonder if India had colleges or cars

or where I had learned my English. The pride of America was in

the fact that almost every house had two cars. Finally I worked

out what I thought was a rib tickling parody. I would say that

I came from a relatively well off middle class family in India;

no cars but two elephants. One of the elephants was old and decrepit

and of not much use except for shopping around town while the

other was a younger, racier model. But at least I didn't have

to ask, Hey Dad, can I have the elephant tonight??

My answer was partly true. We were a middle class family. I was

born in Gujranwala, now in Pakistan. My father had been a star

student at Punjab University from high school to his degree with

honors in Physics. He was innately the sharpest mind I have ever

known and, given the opportunity, might have become a trail-blazing

scientist. But he was one of nine children, so he joined the Punjab

Public Service Commission and rose to become its Secretary.

My father's approach to his religion was rational and analytical.

My mother had a deeply devotional attachment to Sikhism. It took

me years of floundering and rebelling to see that Sikhism had

to be encountered through the dual lenses of faith and intellect.

That was my parents' legacy to us. They also loved books, so we

leared early that becoming voracious readers defined the path

to approval. The parables from Sikhism on which our mother raised

us have stayed with us. I found much later that my paternal grandfather

had been the Stationmaster at Nankana Sahib during the Sikh struggle

to free our gurdwaras from hereditary mahants. He provided food

and shelter to many Sikhs during the struggle and for this was

promptly shipped to Moga by the British government.

I started school at Montessori School in Lahore when I was four

years old. I remember the partition of India; we escaped one week

later on August 22, 1947 with the help of a Muslim truck driver.

My father returned a few days later accompanied by an army escort

and found the house plundered and occupied. He could not believe

that his Muslim neighbors and friends would so quickly put asunder

the ties that bound us.

There is one memory of those days that is as vivid as on the

day that it happened. One afternoon within days of escaping to

Jalandhar, I was playing in the street very close to the railroad

tracks. A train stood on the tracks surrounded by Hindus and Sikhs.

I heard loud explosions that were gunshots. Then I saw a man come

to the tap in the street to wash the blood off his dagger. Later

I leared that a trainload of Hindus and Sikhs was rumored to have

been murdered on its way to India from Pakistan and this was the

payback to Muslims escaping to Pakistan.

Most Sikhs, when they come from India, are at best cultural Sikhs

and know very little of the rudiments of their faith. Living here

in a predominantly non-Sikh milieu they either become better Sikhs

or they abandon Sikhism. Sometimes I wonder what would have happened

to me had I lived my life in India.

So I learned a little of the Sikh ways and also of the lives

of my Jewish and Christian neighbors. I grew to explore the philosophic

depth and the beauty of the Sikh faith. Now I can assert that

I was born a Sikh but I regard myself as a convert to Sikhism.

Four years ago I became an amritdhari Sikh. But this journey is

far from complete and I remain a pilgrim on an endless path.

While a graduate student in Oregon, I met a fellow student who

was working in experimental psychology. Pauline and I married

in 1968 and later moved to New York. A daughter was born to us,

Anna Piar, a name combined from those of the two grandmothers.

She remains the source of much joy and occasional heartache. Our

marriage dissolved when Anna Piar was not quite three.

For a number of years I remained single, ambling around New York

discovering the beauty and the shallowness of our society. In

those single years someone suggested the name of a young Sikh

professional woman. I called her. We talked on the telephone several

times. Finally we thought we should meet. Then she asked: "Before

we meet I want to know - are you a modern Sikh"? I was taken

aback but recovered quickly and thoughtlessly replied, "Of

course, I am modern. I know which fork to use with which dish

at dinner and absolutely never walk out of my house without clothes;

I am not entirely primitive. What exactly do you wish to know"?

We all know what she was really asking, was I a keshdhari Sikh.

I am not surprised to hear such formulations from Sikhs but I

am disappointed. I never thought that not being keshadhari had

anything to do with being modern. The former is an article of

faith for a Sikh, the latter is a state of mind. Needless to say

we never met.

In 1990 a Sikh young lady from Delhi, Neena, was visiting her

sister in Seattle. She came to New York and before she could return

I had a moderate heart attack. I recovered, she stayed and we

got married.

I grew up loving literature and poetry but learned soon enough

that you couldn't make a living in literature. So at the urging

of my father I joined Dental College. In this country, my professional

life moved along fairly steadily. After the PhD, I completed a

two-year stint as a Special Research Fellow of the National Institute

of Health and then joined the faculty of New York University,

where I am now Professor and Coordinator of Anatomical Sciences.

The academic life practices the principle of publish or perish

and I, too, lived by it. Over the years I published and presented

over 100 research papers and reports in professional journals

and in books; I also trained several graduate students and directed

their doctoral research. Within seven year of starting as a new

assistant professor I was a full professor, the only keshadhari

Sikh at that rank at New York University. I also hold Adjunct

Professorships at Columbia University and Cornell University medical

schools and have lectured at many medical and dental colleges

across the country. With such activity come professional affiliations

and recognition and I have enjoyed my share. Whenever I appear

before students to lecture I am aware that I am a Sikh, by definition

a student.

Soon it will be time to retire from a satisfactory professional

career. Has there been discrimination in professional life? Of

course, though not overt, and minimally. Yes, there is a glass

ceiling but it is possible to push against it. I would not be

quite so optimistic in any other society including the land of

my birth, India.

A most traumatic period in my sense of identity came in June

1984 when the Indian Army attacked the Golden Temple. Policies

of the Indian government seemed selectively designed to single

out Sikhs for discrimination, arrests, even torture and killings.

I believe that successive Indian governments, by their shortsighted

policies, brought the country close to fragmentation. For many

Sikhs like me in the diapora this was the defining period for

our sense of self.

It was around 1984 that I leared to separate my Indian identity

from the American ethos that had come to define me. I started

a more serious study of Sikhism - its religion and its culture.

I also became much more active in writing and speaking out about

Sikhism and our Sikh existence outside India.

On looking back I see that an early indication of a serious interest

in Sikhism was when I started to publish reviews of books on Sikhism.

Some essays followed which were meant to chronicle my own growth

along the path of coming to terms with Sikhism. Thanks to Professor

N. Gerald Barrier, a book of essays followed. I was aware that

most books on Sikhism enjoyed an embarrassingly meagre run. But

I was absolutely floored by the response particularly by young

college age Sikhs and my first book went through two reprints.

Then the Centennial Foundation (Canada) issued a revised second

edition. In 2001 they published a second book of a new collection

of my essays on how Sikhism engages many contemporary topics.

It appears that as I am slowly closing my professional career

in teaching and research, a new door is opening, which is equally

if not more gratifying. I cannot possibly describe the pleasure

in exploring and honing the many facets of our Sikh existence

in the diaspora.

The past year has been discomforting and disconcerting. For many

Americans a man in a turban looks too much like Osama bin Laden.

Sikhs have been hassled at airports and in the streets. A man

claiming to be a patriot killed one Sikh in Arizona. Such behavior

is clearly contrary to American values.

As tense as things get on the street sometimes, America remains

a most tolerant and open society. Recently, I met a clearly educated

man on the street. After chatting a while he turned serious and

somewhat apologetically asked, "Tell me, when your people

came here why didn't they leave their religion back home"?

I was flabbergasted for a moment. Finally I turned to him and

said: "Yes, I can answer that equally briefly. Tell me, when

your people came here why didn't they leave their religion back

home"? For a moment he was nonplussed but then he smiled.

"You have a point," he said.

It has been an extraordinary 42 years and now I know no other

home than here. I have changed internally. Some Indians on the

street who appear pseudo-westernized look at my external self

and wonder if I have remained untouched by America. My Indian

friends remind me how American I have become in my ways while

my American friends smile at what they call my Indian ways of

thinking. I reckon they are both right.

When I talk to young Sikhs my message to them that I have distilled

from my lifetime here is that, " Much as it is possible to

be a good Jew and a good American, or a good Christian of any

sort and a good American, it is just as possible to be a good

Sikh and a good American; the two terms are not mutually exclusive."

November 1, 2002

In Nov. of 2003 he made a presentation at the Sikh American Society

of Georgia, US